A Province in an old Postcards

There it stands now, in beauty bright

For the very first time, the story of an ancient city comes alive through vintage postcards.

Unforgettable strolls through Vladimir — mysterious, yet so dear to the heart.

Each old postcard invites us to rediscover the familiar streets of the city center, revealing them in a new and captivating light.

A Province in an old Postcards

There it stands now, in beauty bright

Автор текста и стихов Тимофеева Татьяна Петровна

Авторы планов города:

Ткачёв Юрий Константинович

Денисов Анатолий Егорович

Год выпуска: 1997

192 с. Тираж 5000 экз.

книга доступна только в составе полной коллекции серии книг «Губерния в старой открытке». Общая стоимость коллекции всех книг серии 35 000 руб.

One ought to walk barefoot on that sort of ground. lt was said of such ground as this: «Put off thy sho,

“Vladimir in an Old Postcard”

from оff thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground. Неrе on this hill the Кiev prince Vladirmir Svyatoslavovitch founded the city. lt came to pass in the year 990 or 992, shortly after the

baptism of the Кiev people in the river Dnieper. «The wellspring of gospel did owerflow, and spread over the entire earth, and reached out bourn» (Metropolitan Illarion, XI century А.О.). Аnd

it is in connection with the baptism of its inhabitants that the city of Vladimir is

mentioned in the chronicles. The latter also refer to another prince, Vladimir

Monomachus who, а century later, rebuilt the city anew. Не did not found the

city, but rather fortified it.

The monastery of the Nativity had been foremost among Russian monasteries, and only as late as 1561 yielded its preeminence to the Troiyse-Sergiev monastery, and then in 1720 to the monastery of Alexander Nevsky as well.

“Vladimir in an Old Postcard”

Nevertheless, it had always remained under the authority and patronage of metropolitans and patriarchs. In the mid-eighteenth century it became the residence of Vladimir Bishops. For а long time it had been the repository for the marvellous relic of Prince Alexander Nevsky, who was buried in the cathedral church in 1263 and sainted in

ln 1723 his remains were transferred to St. Petersburg.

And ultimately, since the twelfth century, right in the middle of Bolshaya Street stands fmn the Golden Gate, commencing it in time and space. Built by Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky simultaneously with the new citadel, it served as the main fortified entrance to the town, but ceased to bе used for this purpose in the eighteenth

“Vladimir in an Old Postcard”

century. Numerous passages were cut through the citadel ramparts; they were intersected with footpaths, p!anted all over, filled up and overgrown. The other turreted gates — the Silver Gate (Serebryaniye Vorota) in the south-east, the Volga Gate in the south, the Copper (Medniye Vorota) and the Irina (Jrininskiye Vorota) gates in the north had

long before been destroyed.

The Golden Gate — the main gate of VIadimir at the time when it was the capital of Andrei Bogolyubsky’s great principality — for some mysterious reason faces west. lt could not have been Moscow that made this majestic edifice look оп to it. At that time Moscow was а tiny speck of life in the midst of the Zalessky region. А different luminary attracted the gate. What was that? Could it Ье that it was the Кievan state and the Great Prince Yaroslav’s capital

“Vladimir in an Old Postcard”

with а similar layout and its western Golden Gate, monasteries bearing the same names, that served as the model for the new royal citadel in the western part of the old town of Vladimir? God knows!

Among the broad water-meadows at the confluence of the Nerl and Klyazma stands the beautiful Church of the Intercession ( 1165), one of the most poetic creations of old Russian architecture. lts elegant forms, graceful outline and carved decorations transcend the weight and solidity of stone. The reliefs, among them the band of blind arcading, the female masks, Кing David surrounded bу lions and eagles, combine to tell а sermon whose meaning is по longer to Ье fu lly comprehended; to а layman, David, the biblical prophet and psalmist, seems to bе the only intelligible figure

“Vladimir in an Old Postcard”

here. The Church of the Intercession was originally one in а series of buildings exemplifying the stupendous plan of Prince Andrei pervading the architecture, theology and politics of his reign.

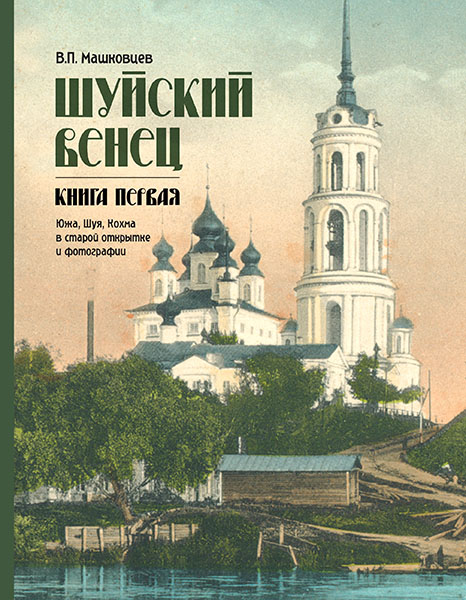

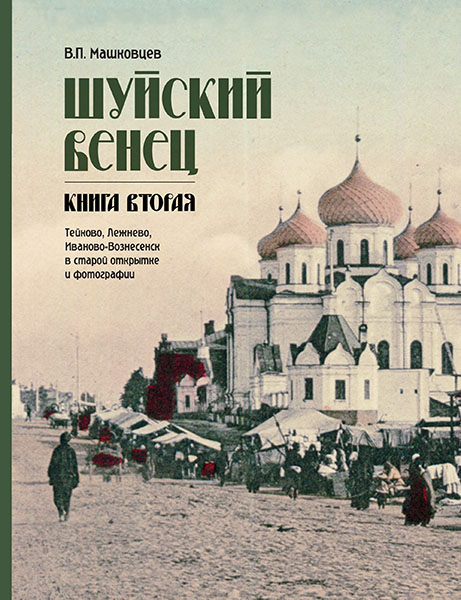

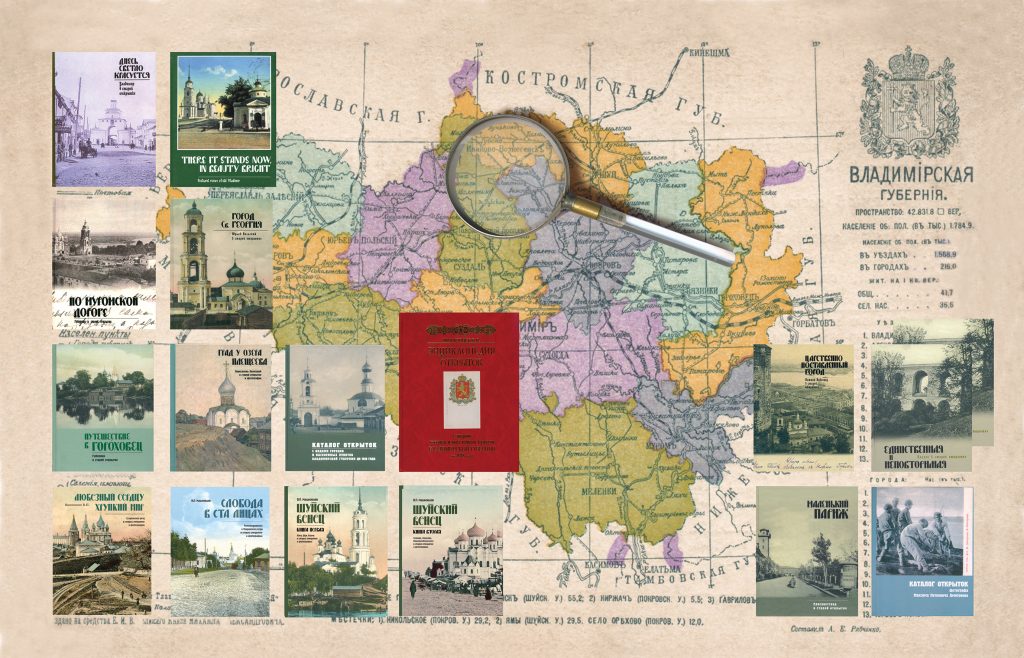

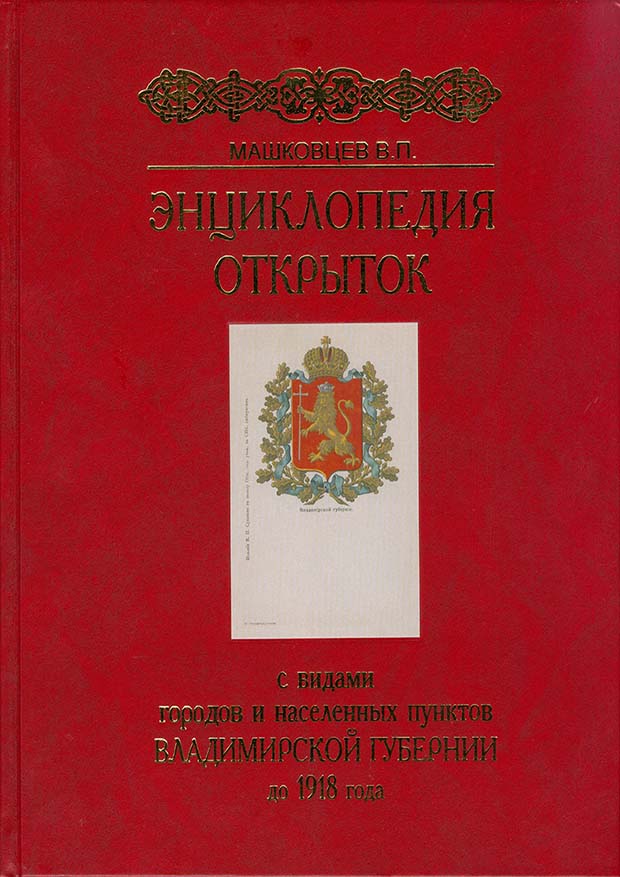

губерния в старой открытке

Вам также могут понравиться

Ниже — список книг, дополняющих тематику данной книги.